A film review by Anthony Lane for NewYorker.com on August 22, 2016.

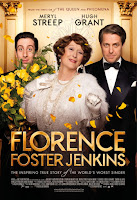

The defining talent of Florence Foster Jenkins (1868-1944) was that she had no talent. Of this she was unaware. As a singer, she could not hit a note, yet somehow she touched a chord—murdering tune after tune, and drawing a legion of fans to the scene of the crime. Never has ignorance been such cloudless bliss; her self-delusion, buoyed by those about her, amounted to a kind of genius, and the story of that unknowing has now inspired a bio-pic. Florence Foster Jenkins, written by Nicholas Martin and directed by Stephen Frears, stars Meryl Streep in the title role. Who better to play the incompetent Florence than someone whose plenitude of gifts has been an article of faith for almost forty years?

There is something of a pattern here, and a risk. If you want to see real-life women of a certain age incarnated by the most formidable actresses, then Frears is your man. Think of Philomena (2013), in which Judi Dench played a simple soul on a quest for her long-lost son. The tale was astutely told, though it couldn’t avoid a murmur of condescension. Seven years earlier, in Frears’s The Queen, Helen Mirren took the part of Elizabeth II and lent it a musing reflectiveness that, however winning, seemed slightly at odds with the dutiful pragmatist, braced by common sense, who occupies the British throne. In both cases, sheer dramatic skill threatened to overwhelm the facts of the character, and you half-expect Streep to follow suit. Yet her performance is the most successful of the three; not once do you feel that she knows better than Florence—that the leading lady is looking down on her creation, as it were, with an arch of the eyebrow or a taunting glint in the eye. On the contrary, Streep is right there, solidly invested in the folly of Florence’s dreams. When she declares that music has been, and is, my life, you believe her.

The first person we meet is not the heroine but her husband, St. Clair Bayfield (Hugh Grant), who was once an actor and likes to keep his hand in. Resplendent in white tie and tails, he recites a speech from Hamlet, for the benefit of guests at a New York soirée. His delivery is, let us say, more impassioned than convincing, and we are instantly aware that here is someone who has fallen short. The most touching thing is that he doesn’t seem to mind. To realize that one is second-rate can be an epiphany of sorts, or, at least, an immense relief. St. Clair claims to be free from the tyranny of ambition, and you can see his point. In any case, he has found a higher calling. His earthly task is to serve the needs of his wife, who inherited money and, with it, a plush sense of entitlement. All goes well until, one evening, an old need rears its head again. The tyranny is back. Florence wants to sing.

Frears, whose slyness has deepened with the years, is not averse to teasing. Notice how he delays the first caterwaul, like a maker of war films who waits to unleash the opening boom of artillery. Before Florence can start her glass-shattering routine, she requires an accompanist, and the movie pauses to consider Cosmé McMoon (Simon Helberg), a reedy young pianist who applies for the job. Offered a wage of ludicrous generosity, he leaves Florence’s apartment, in Manhattan, with a dizzy grin on his face, and the camera, savoring the moment, watches him drift down the street. Helberg has the long sad mug of a mime and the body of a boy; instead of strolling, he seems to hover along, with his hands held stiffly by his side. (You can imagine him in silent pictures, as a hopeful stooge.) When Florence finally lets rip, what Frears attends to is not just the noise that she creates, reminiscent of a hyena giving birth, but the awestruck expression on Cosmé’s face. Why, he asks himself, is nobody laughing?

The answer, as usual, is money. David Haig, a brisk and cheering presence, plays Carlo Edwards, a vocal coach from the Metropolitan Opera, who regularly provides Florence with private tuition. This he must do, for she is an effusive patron, and his plaudits, as she lurches ferociously off key, are small masterpieces of ambivalence: There’s no one quite like you, You’ve never sounded better, and the ominous You’ll never be more ready. For Florence has plans that soar beyond the limits of her drawing room. In the course of the film, she performs first before a cluster of aging acquaintances, many of them blessedly hard of hearing, and, later, at Carnegie Hall, which is packed, at Florence’s request, with soldiers and sailors, most of them blessedly drunk.

Believe it or not, this did indeed take place, on October 25, 1944: a holy day in the annals of ineptitude. (You are taken aback by the Second World War uniforms, and by St. Clair’s report that Florence has sold out faster than Sinatra, because her demeanor, like her décor, belongs to an earlier age.) If Florence has remained a cult, it is thanks to her bravado in plowing ahead, regardless of her faults. That is certainly the view of Agnes (Nina Arianda), the wife of a rich meathead, who springs to her feet at the concert, rebukes the crowd for jeering, and whips up a storm of applause. Though the film as a whole is less raucous than Agnes, it obeys her instructions, bestowing benign approval on its subject. The result is at once a work of efficient charm and, to those of us who treasured Frears in his more acerbic phase, a mild disappointment. Would the man who made My Beautiful Laundrette (1985), The Grifters (1990), and two foul-tongued Roddy Doyle adaptations have been quite so tolerant of Florence’s fancies? After all, the wealthy of today are equally flattered and indulged, and, as Frears proved in Dangerous Liaisons (1988), costume dramas are no excuse for softness. They need a drop of venom in their veins.

The best news about Florence Foster Jenkins is that, just when admirers of Hugh Grant were asking if the poor guy would ever get a role of any ripeness, he plucks a peach. The dithering that bore him through Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994) and Notting Hill (1999) arose not merely from indecision but from a stutter of the spirit—a genuine horror of doing the wrong thing. That fear comes to fruition in St. Clair: his wife does wrong every time she opens her mouth onstage, but he reassures her, time and again, that she is in the right. He pays music critics to be nice; when one of them, refusing the bribe, writes a mean review, St. Clair tries to destroy every copy of the paper in the neighborhood. For twenty-five years I have kept the mockers and scoffers at bay, he says. His love, though true, is a perpetual agony, and maybe no one but Grant, writhing with misplaced chivalry, could bring such reverence to life. Florence may have been a one-joke wonder, and, to be honest, there is only just enough of her to fill a movie. In the eyes of her husband, however, she is no joke at all. [Lane’s rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars]

Labels: biography, comedy, drama, music

No comments:

Post a Comment